When it comes to improving security of websites one of the problems we see is that real issues do not receive the attention they should, while other issues, that are of little to no concern, do get attention. Often times it is security companies that play an important role in this happening, when they should be helping to push against this.

When it comes the security of WordPress websites one of the big problems that exists is that vulnerabilities in plugins that are being exploited do not always get fixed in a timely manner or in some cases ever. A recent example of that comes with an arbitrary file upload vulnerability that exist in the most recent version in the plugin Delete All Comments. Through that vulnerability a hacker could upload files of their choosing and then do almost anything they want with the website. The security company NinTechNet spotted the vulnerability while cleaning up a website was hacked through it on November 20. They notified the developer, but received no response from them (one possible explanation for the vulnerability being in the plugin is that it was actually intentional put in the plugin, though it could just as easily be unintentional).

NinTechNet then notified the Plugin Directory and the plugin was removed from that. That prevents anyone not using the plugin already from installing and making themselves vulnerable, but what happens for the 30,000+ websites that already were using it according to wordpress.org? Nothing. The people running those websites are left unaware that their website is open to be exploited. Amazingly this isn’t because no one had brought up this issue. We raised it back in March of 2012. Shortly after that we proposed on the Ideas section of the WordPress website that people be alerted people when their websites are using plugins that have been removed from the Plugin Directory and providing at least general reason why it was removed. Shortly afterwords it was marked as “Good idea! We’re working on it” and it was stated that it was being worked on. By six months ago the same person said:

We cannot provide this service at this time.

IF an exploit exists and we publicize that fact without a patch, we put you MORE at risk.

Strangely the idea is still marked as “Good idea! We’re working on it”, which keeps it from being listed on prominently on front page of Ideas section (where it would be tied for the second most popular idea that hasn’t been greenlit and where more people would see that the issue is being left unaddressed).

There is another option, the Plugin Directory can put out a fixed version when the developers doesn’t do that, but they rarely do that, don’t seem to have provided any sort of public criteria on when they would do that, and someone on the WordPress side even deleted a comment we made in regards to the issue at one point.

In the meantime if you install the companion plugin for our Plugin Vulnerabilities service you get warned in situation like this as we include information on vulnerabilities that looked to be being exploited to the free data included with that (last week we also added data on vulnerabilities that look to being exploited in the current version of a plugin with 40,000+ installs and another with 20,000+ active installs).

If these got more public attention we have hard time believing that WordPress would continue to leave people vulnerable, but that is the situation we and everyone else is dealing with until such time.

If you are thinking that a security plugin would protect against this type of thing, think again. We tested the ability of 15 security plugins to prevent exploitation of the vulnerability in Delete All Comments last week and found that none of them stopped it.

One of those plugins that didn’t stop it was Wordfence, a plugin with 1+ million active installs, which is describe on the its main page on the Plugin Directory thusly:

Secure your website with Wordfence. Powered by the constantly updated Threat Defense Feed, our Web Application Firewall stops you from getting hacked.

That unqualified claim is that it stops from you getting hacked is clearly false as not only that test against the vulnerability in Delete All Comments shows. In three other tests we have done, in either Wordfence provided no protection or the protection was easily bypassed. It is also worth noting that from everything we have seen Wordfence’s Threat Defense Feed misses many plugin vulnerabilities.

So how do you get over 1 million installations of plugin that doesn’t actually do what it claims to do. Well what appears to be an important role in that is that Wordfence simply makes up threats and then claims to protect against them.

Brute Force Attacks Are Not Happening

Take for instance last Friday when they put out a post “Huge Increase in Brute Force Attacks in December and What to Do“, which claimed:

At Wordfence we constantly monitor the WordPress attack landscape in real-time. Three weeks ago, on November 24th, we started seeing a rise in brute force attacks. As a reminder, a brute force attack is one that tries to guess your username and password to sign into your WordPress website.

Of course they have the solution for this:

If you install the free version of Wordfence, you are automatically protected against brute force attacks. It’s that simple. We also automatically block the worst offenders completely, and we share some information below on who those are.

There is just one problem with all of that, brute force attacks against WordPress admin logins are not actually happening. Back when we originally discussed the fact that security companies are falsely telling people brute force attacks are happening in August we used as an example from Wordfence in January, so Wordfence has been using this falsehood to push their product for some time.

We wrote in that post:

To understand how you can tell that these brute force attacks are not happening, it helps to start by looking at what a brute force attack involves. A brute force attack does not refer to just any malicious login attempt, it involves trying to login by trying all possible passwords until the correct one is found, hence the “brute force” portion of the name. To give you an idea how many login attempts that would take, let’s use the example of a password made up of numbers and letters (upper case and lower case), but no special characters. Below are the number of possible passwords with passwords of various lengths:

- 6 characters long: Over 56 billion possible combinations (or exactly 56,800,235,584)

- 8 characters long: Over 218 trillion possible combinations (218,340,105,584,896)

- 10 characters long: Over 839 quadrillion possible combinations (839,299,365,868,340,224)

- 12 characters long: Over 3 sextillion possible combinations (3,226,266,762,397,899,821,056)

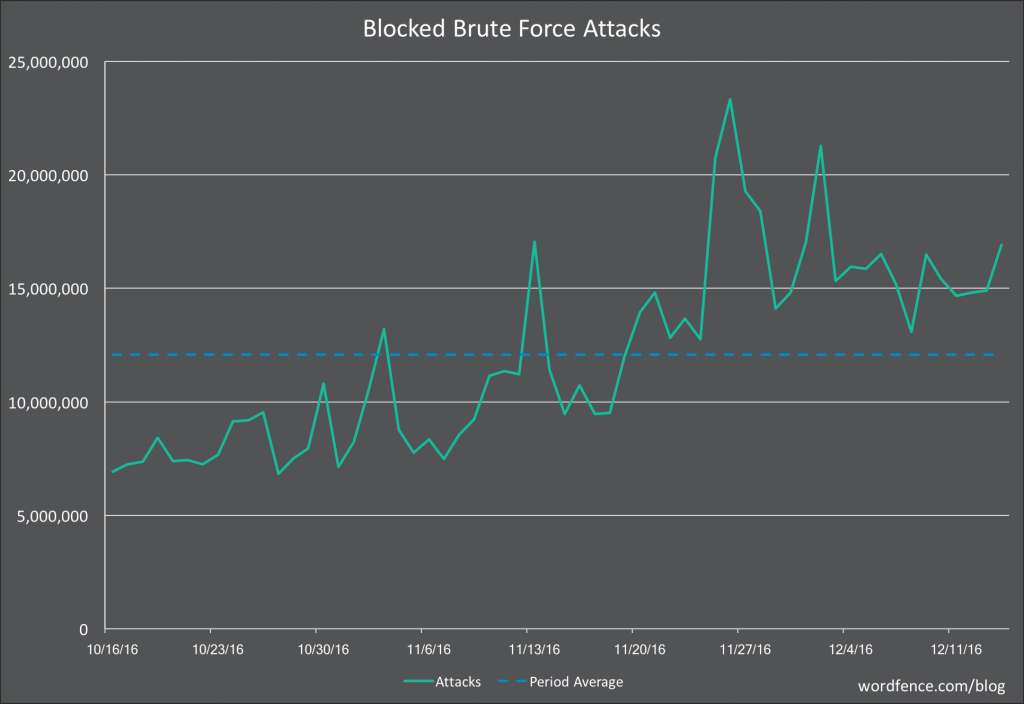

The chart of login attempts in Wordfence post from last week show only millions of login attempts per day:

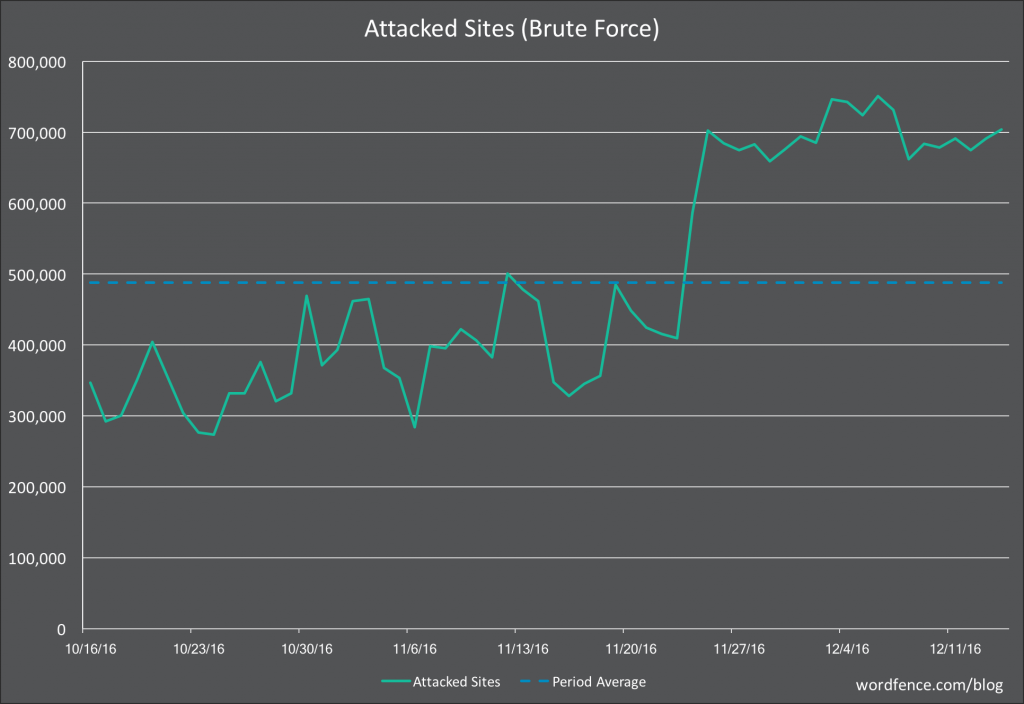

It would take a long time for that to get to the amount needed for a brute force attack, but wait, those are not against one website, those are across hundreds of thousands of websites:

So we are talking about an average of 10s of attempts per website, which is never going to amount to a brute force attack.

So what is actually going on? Well based on the number of attempts and by looking at what username/password combinations were used in actual malicious login attempts it looks like most of these are actually dictionary attacks. A dictionary attack involves trying to log in using common passwords.

Knowing what type of attack is important because how you prevent them and the level concern you should have is very different for different types. With what is actually happening, dictionary attacks, all you need to protect yourself is to use a strong password, otherwise you can simply ignore this.

That might explain why Wordfence is misleading people, if they told people the truth they wouldn’t be a need for them to install their plugin (and then possibly sign up for Wordfence’s paid service). The other possibility, which seems just as likely based on what else we have seen, is Wordfence simply doesn’t have a good understanding of security. That could also explain why they don’t understand why it is inappropriate to make an unqualified claim that their plugin “stops you from getting hacked” when that would that would be able to truly stop any hack is next to impossible.

If you look at the comments on Wordfence’s recent post you can see they have successfully mislead a lot of people into believing their false claim, which makes it even harder to get people to focus on real issues and that means more websites are going to get hacked that should not have.

I’m beginning to think your just rehash the same blog post again and again.

“X company is spreading falsehoods about Y attack, sign up for our Plugin Directory to know that you’re vulnerable but can’t fix it.”

To the layperson, they don’t give a crap if it’s a dictionary attack or a brute force attack. An attack is an attack is an attack. If they happen to have some passwords in that dictionary and wordfence does stop it, is there not value in that? I could understand a few posts about wordfence but holy moly i swear like half your blog is just about bad mouthing them. Change topics already.

It isn’t clear why you think it okay to mislead (or outright lie) to people about what is actually going, but from our experience the lay person does care. We deal with people that come to worried they are hacked because they have gotten a message from a security plugin that there are brute force attacks against their website. When we explain to them what is actually going on it clears things up, as they are already are using a strong password. It seems that scaring them may be part of the intent of misleading people about brute force attacks happening.

If you are using a password that is in a dictionary then the best solution is to change to a strong password, not install a plugin. There are a number of reasons for that, including that each time you add a plugin you introduce more potential for vulnerabilities on your website (the Wordfence plugin has been found to have vulnerabilities of its own in a number of instances).

Since you don’t like what we choose to discuss on our blog, stop reading it, no one is forcing you to read it. Also, our blog isn’t anywhere near half about Wordfence (it might that much about SiteLock though).

As for our Plugin Vulnerabilities service, we are actually always happy to help our customers deal with any vulnerabilities that exist in the current versions of plugins they use, whether that being putting a fix in place or something else. We also work to get the plugins fixed, so even if you are not our customer you can eventually get protected. We didn’t suggest people sign up for it in this post, just install the companion plugin, which doesn’t require any sign up.

Don’t you mislead your readers with stretched and half truths? All with the intent of promoting your own products and services?

In case anyone cares, dictionary attacks have nothing to do with words actually being in a dictionary. Any user can create their own dictionary. A common occurrence when you take into consideration the number of user and password lists currently being distributed.

Looking at wpvulndb it seems most of the WordFence vulns go back to 2014: https://wpvulndb.com/search?utf8=%E2%9C%93&text=wordfence and most don’t look like big issues. Even if the list is not accurate, aren’t you subscribing to the same tactics you claim they are taking?

Isn’t it also said that vulnerabilities exist in all code?

We don’t actually, that is what Wordfence is doing, as we described in this post. If we were doing that it should be easy for you to provide examples, instead of asking loaded questions like this.

It isn’t clear what your point is supposed to be here, since we didn’t say that a dictionary involves words from a dictionary. Instead we said “A dictionary attack involves trying to log in using common passwords.”. A brute force attack doesn’t involve physical brute force either, should we have noted that as well?

If anyone want to see what types of password are used in a real dictionary attack against WordPress we have a new post with a couple of examples.

Again, it isn’t clear what your point is supposed to be here. What we said is “the Wordfence plugin has been found to have vulnerabilities of its own in a number of instances” and you linked to a page that confirms it, as the page has 11 different entries for vulnerabilities in Wordfence (at least one of those entries is for “multiple vulnerabilities”). And that page clearly isn’t comprehensive, in a quick check we found an example of a vulnerability from 2015 and one from 2016 (that one was rated as being of “Medium” severity by Wordfence itself), so there are more than even listed on that page.

If someone said that, they are wrong. Think of a simple hello world program, is there going to be a vulnerability in it? But for the sake of argument let say that is true, that would be a great reason why it is so wrong for Wordfence to push a false threat and then tell people the solution is to install their plugin, as those websites are now more vulnerable then they were before, when the real threat, dictionary attacks, is easily protected against without introducing new vulnerabilities.

You could be right about Wordfence. They could be installing false softwares in people’s sites and make it seems like people are been hacked.

Our post doesn’t relate to what you are claiming and we highly doubt that would happen with them or any other security company.