When it comes to why website security is in such bad shape, one issue that we have a hard time understanding is why so many people would use security services that are not marketed with evidence, much less evidence from independent testing, that they are actually effective at providing security they claim to provide. It would seem that people would want some assurance that what they are paying for works, but that doesn’t appear to be the case as many people use them and we have yet to run across one company providing a service that makes a general claim that it will protect websites that is backed with evidence. At the same time we have seen plenty of evidence from various sources that indicates that these services at best provide limited protection.

One of the most serious implications of all that is that a lot of money is going to companies that are not doing much in terms of improving security and in all likelihood if that same money was going to companies that were actually improving security then security would be in much better shape than it is now even for those not using any service and it would be getting even better from there.

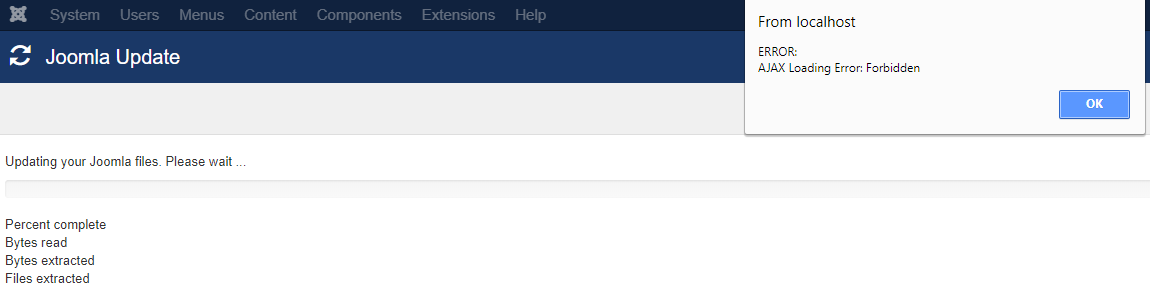

Another implication of that we have been running into quite a bit recently, is that those security services cause all sorts of complications for those using them without them getting the security benefit that should be the tradeoff for that. We recently had someone we were working with that had a security service on their website that made it harder to do something that would actually improve the security of the website and was blocking users from taking basic actions. At the same time, any protection the service could actually provide for their website could be easily bypassed.

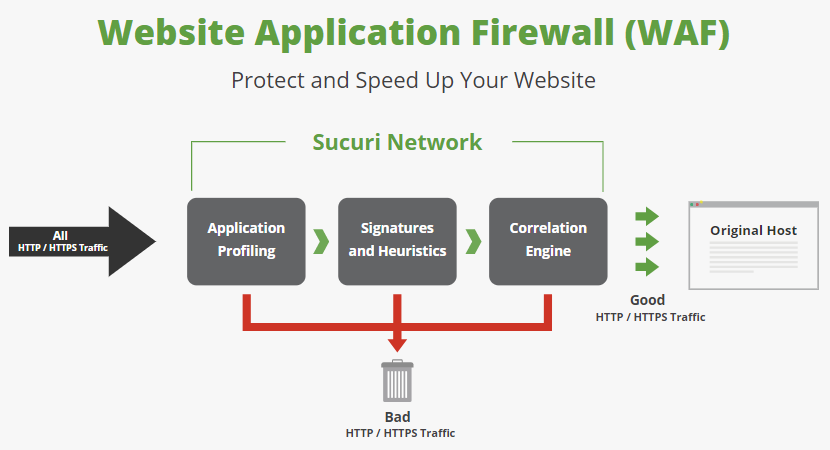

Another recent incident involved someone thinking that their website contained malware due to a recently added content delivery network (CDN)/web application firewall (WAF) service provided by a company named StackPath, which lead to them contacting us to see about getting it cleaned up. If they had contacted a less scrupulous company that could have lead to them spending more money on a cleanup service they didn’t really need.

Before we get in to more detail on that part of this, we should point out that StackPath is yet another security company that doesn’t promote their service with any evidence that is effective, as can be seen by visiting the page for their WAF. What seems even more telling is one of the company’s most recent blog posts, in which the CEO (who is a lawyer, not a security specialist) touts how many customers they have added and how much revenue they are bringing in, but nothing about actually providing security or improving security. Another part of that post is rather odd:

- Our VPN business is on fire! We have increased our consumer VPN business 100% year after year and signed exclusive enterprise VPN partnerships, such as the recent agreement with Eero.

A VPN services seems to be unrelated to how the company otherwise promotes what it does and that service seem to go otherwise unmentioned on their website, which makes us wonder if this company is just sort of thrown together and that seems like an indication that they might not be a company that has the capability to provide good security.

This Looks Like Malware

What lead the person to believe that they might have malware on their website and then contact us was that they started seeing requests for URLs like this:

/index.php?_route_=sbbi/&sbbpg=sbbShell&gprid=cj&sbbgs=h436dbc8688a162192e9854e39ab7c45df61&ddl=2

The website was OpenCart based, so some of that URL format looks to based on how URLs for that sofrware are formatted. On other websites using the same services they might look different, here is another example:

/sbbi/?sbbpg=sbbShell&gprid=IA&sbbgs=&ddl=17785633

In looking into this we originally found a reference to this be connected to a CDN. In later looking into things further it was a bit confusing as to who might behind this, which seems to be due to multiple corporate changes. The “sbb” part of that looks to refer to SiteBlackBox, which renamed itself to FireBlade and then was acquired by Stackpath.

What gets served in those URLs for a short time is something that looks like this:

<html lang=”en”> <head> <title>env</title> <meta http-equiv=”Content-Type” content=”text/html;charset=UTF-8″> <meta name=”robots” content=”noindex, nofollow”> </head> <body> <script type=”text/javascript”> window.parent.sbrmp=true;var _0x1d10=[“\x64\x6F\x63\x75\x6D\x65\x6E\x74”, “\x65”, “\x6D\x6F\x76”, “\x6F”, “\x70\x61\x72\x65\x6E\x74”, “\x39”, “\x6D\x6F\x75\x73”, “\x6E”, “\x61\x64\x64\x45\x76\x65\x6E\x74\x4C\x69\x73\x74\x65\x6E\x65\x72”, “\x67\x65\x74\x44\x61\x74\x65”, “\x73\x65\x74\x44\x61\x74\x65”, “”, “\x74\x6F\x47\x4D\x54\x53\x74\x72\x69\x6E\x67”, “\x63\x6F\x6F\x6B\x69\x65”, “\x3D”, “\x3B\x65\x78\x70\x69\x72\x65\x73\x3D”, “\x67\x65\x74”, “\x67\x65\x74\x45\x6C\x65\x6D\x65\x6E\x74\x42\x79\x49\x64”, “\x61\x74\x74\x61\x63\x68\x45\x76\x65\x6E\x74”, “\x69\x5F\x37\x32\x36\x32\x33\x65\x76”, “\x72\x65\x6D\x6F\x76\x65\x45\x76\x65\x6E\x74\x4C\x69\x73\x74\x65\x6E\x65\x72”, “\x64\x65\x74\x61\x63\x68\x45\x76\x65\x6E\x74”];function mark(){return ancestor[_0x1d10[0]];};var txte=_0x1d10[1];var cnt=0;function MouseMove(_0xa880x5){cnt++;if(isFieldIntact()){i_72623ev9=getFrosen();hideOWL(i_72623ev9);stop();};};var eve2=_0x1d10[2];var txto=_0x1d10[3];var ancestor=markPointer();function markPointer(){return window[_0x1d10[4]];};var lie=false;var selecedRound=_0x1d10[5];var eve1=_0x1d10[6];var nchar=_0x1d10[7];function iseventlistener(_0xa880xf){return _0xa880xf[_0x1d10[8]];};function isFieldIntact(){if(isattachevent(mark())){if(cnt > 1){return true;}else{return lie;};};return true;};function hideOWL(_0xa880x12){var _0xa880x13=new Date();_0xa880x13[_0x1d10[10]](_0xa880x13[_0x1d10[9]]()+1);var _0xa880x14=_0x1d10[11]+nullRound+selecedRound+iseequal+escape(i_72623ev9)+(nvrborn(1)? noone : killhim)+_0xa880x13[_0x1d10[12]]();mark()[_0x1d10[13]]=_0xa880x14;};function getFrosen(){return 75;};function start(){if(mark()){processstuff(mark(), eve1+txte+eve2+txte, MouseMove);};};var iseequal=_0x1d10[14];var killhim=_0x1d10[15];function testWhc(){return document[_0x1d10[17]](_0x1d10[16]);};function processstuff(_0xa880x1b, _0xa880x1c, _0xa880x1d){if(iseventlistener(_0xa880x1b)){_0xa880x1b[_0x1d10[8]](_0xa880x1c, _0xa880x1d, lie);}else{if(isattachevent(_0xa880x1b)){_0xa880x1b[_0x1d10[18]](txto+nchar+_0xa880x1c, _0xa880x1d);};};};var noone=_0x1d10[11];function nvrborn(_0xa880x20){return(_0xa880x20==null);};var i_72623ev9;var nullRound=_0x1d10[19];function stop(){if(mark()){unprocessstuff(mark(), eve1+txte+eve2+txte, MouseMove);};if(testWhc()){alert(mark()[_0x1d10[13]]);};};function isattachevent(_0xa880xf){return _0xa880xf[_0x1d10[18]];};function unprocessstuff(_0xa880x1b, _0xa880x1d, _0xa880x1c){if(iseventlistener(_0xa880x1b)){_0xa880x1b[_0x1d10[20]](_0xa880x1d, _0xa880x1c, lie);}else{if(isattachevent(_0xa880x1b)){_0xa880x1b[_0x1d10[21]](txto+nchar+_0xa880x1d, _0xa880x1c);};};};start();</script>;</body> </html>

It isn’t all that surprising that would be seen as being malicious since it has multiple layers of obfuscation and nothing that identifies what it is related to.

One of those layers of obfuscation is an array containing hex encoded values. Converting those to alphanumeric characters leads to it looking like this:

<html lang=”en”> <head> <title>env</title> <meta http-equiv=”Content-Type” content=”text/html;charset=UTF-8″> <meta name=”robots” content=”noindex, nofollow”> </head> <body> <script type=”text/javascript”> window.parent.sbrmp=true;var _0x1d10=[“document”, “e”, “mov”, “o”, “parent”, “9”, “mous”, “n”, “addEventListener”, “getDate”, “setDate”, “”, “toGMTString”, “cookie”, “=”, “;expires=”, “get”, “getElementById”, “attachEvent”, “i_72623ev”, “removeEventListener”, “detachEvent”];function mark(){return ancestor[_0x1d10[0]];};var txte=_0x1d10[1];var cnt=0;function MouseMove(_0xa880x5){cnt++;if(isFieldIntact()){i_72623ev9=getFrosen();hideOWL(i_72623ev9);stop();};};var eve2=_0x1d10[2];var txto=_0x1d10[3];var ancestor=markPointer();function markPointer(){return window[_0x1d10[4]];};var lie=false;var selecedRound=_0x1d10[5];var eve1=_0x1d10[6];var nchar=_0x1d10[7];function iseventlistener(_0xa880xf){return _0xa880xf[_0x1d10[8]];};function isFieldIntact(){if(isattachevent(mark())){if(cnt > 1){return true;}else{return lie;};};return true;};function hideOWL(_0xa880x12){var _0xa880x13=new Date();_0xa880x13[_0x1d10[10]](_0xa880x13[_0x1d10[9]]()+1);var _0xa880x14=_0x1d10[11]+nullRound+selecedRound+iseequal+escape(i_72623ev9)+(nvrborn(1)? noone : killhim)+_0xa880x13[_0x1d10[12]]();mark()[_0x1d10[13]]=_0xa880x14;};function getFrosen(){return 75;};function start(){if(mark()){processstuff(mark(), eve1+txte+eve2+txte, MouseMove);};};var iseequal=_0x1d10[14];var killhim=_0x1d10[15];function testWhc(){return document[_0x1d10[17]](_0x1d10[16]);};function processstuff(_0xa880x1b, _0xa880x1c, _0xa880x1d){if(iseventlistener(_0xa880x1b)){_0xa880x1b[_0x1d10[8]](_0xa880x1c, _0xa880x1d, lie);}else{if(isattachevent(_0xa880x1b)){_0xa880x1b[_0x1d10[18]](txto+nchar+_0xa880x1c, _0xa880x1d);};};};var noone=_0x1d10[11];function nvrborn(_0xa880x20){return(_0xa880x20==null);};var i_72623ev9;var nullRound=_0x1d10[19];function stop(){if(mark()){unprocessstuff(mark(), eve1+txte+eve2+txte, MouseMove);};if(testWhc()){alert(mark()[_0x1d10[13]]);};};function isattachevent(_0xa880xf){return _0xa880xf[_0x1d10[18]];};function unprocessstuff(_0xa880x1b, _0xa880x1d, _0xa880x1c){if(iseventlistener(_0xa880x1b)){_0xa880x1b[_0x1d10[20]](_0xa880x1d, _0xa880x1c, lie);}else{if(isattachevent(_0xa880x1b)){_0xa880x1b[_0x1d10[21]](txto+nchar+_0xa880x1d, _0xa880x1c);};};};start();</script>;</body> </html>

Placing those array values into the code below it gets you this:

<html lang=”en”> <head> <title>env</title> <meta http-equiv=”Content-Type” content=”text/html;charset=UTF-8″> <meta name=”robots” content=”noindex, nofollow”> </head> <body> <script type=”text/javascript”> window.parent.sbrmp=true;var _0x1d10=[“document”, “e”, “mov”, “o”, “parent”, “9”, “mous”, “n”, “addEventListener”, “getDate”, “setDate”, “”, “toGMTString”, “cookie”, “=”, “;expires=”, “get”, “getElementById”, “attachEvent”, “i_72623ev”, “removeEventListener”, “detachEvent”];function mark(){return ancestor[document];};var txte=e;var cnt=0;function MouseMove(_0xa880x5){cnt++;if(isFieldIntact()){i_72623ev9=getFrosen();hideOWL(i_72623ev9);stop();};};var eve2=mov;var txto=o;var ancestor=markPointer();function markPointer(){return window[parent];};var lie=false;var selecedRound=9;var eve1=mous;var nchar=n;function iseventlistener(_0xa880xf){return _0xa880xf[addEventListener];};function isFieldIntact(){if(isattachevent(mark())){if(cnt > 1){return true;}else{return lie;};};return true;};function hideOWL(_0xa880x12){var _0xa880x13=new Date();_0xa880x13[setDate](_0xa880x13[getDate]()+1);var _0xa880x14=+nullRound+selecedRound+iseequal+escape(i_72623ev9)+(nvrborn(1)? noone : killhim)+_0xa880x13[toGMTString]();mark()[cookie]=_0xa880x14;};function getFrosen(){return 75;};function start(){if(mark()){processstuff(mark(), eve1+txte+eve2+txte, MouseMove);};};var iseequal==;var killhim=;expires=;function testWhc(){return document[getElementById](get);};function processstuff(_0xa880x1b, _0xa880x1c, _0xa880x1d){if(iseventlistener(_0xa880x1b)){_0xa880x1b[addEventListener](_0xa880x1c, _0xa880x1d, lie);}else{if(isattachevent(_0xa880x1b)){_0xa880x1b[attachEvent](txto+nchar+_0xa880x1c, _0xa880x1d);};};};var noone=;function nvrborn(_0xa880x20){return(_0xa880x20==null);};var i_72623ev9;var nullRound=i_72623ev;function stop(){if(mark()){unprocessstuff(mark(), eve1+txte+eve2+txte, MouseMove);};if(testWhc()){alert(mark()[cookie]);};};function isattachevent(_0xa880xf){return _0xa880xf[attachEvent];};function unprocessstuff(_0xa880x1b, _0xa880x1d, _0xa880x1c){if(iseventlistener(_0xa880x1b)){_0xa880x1b[removeEventListener](_0xa880x1d, _0xa880x1c, lie);}else{if(isattachevent(_0xa880x1b)){detachEvent](txto+nchar+_0xa880x1d, _0xa880x1c);};};};start();</script>;</body> </html>

There would still be several steps to fully make that easily human readable, but based on that, it looks like code try to detecting if a human is making a requests and setting a cookie based on that. It isn’t clear what the purpose of obfuscating it is, since someone trying to evade the protection provided by that likely wouldn’t be hindered in a serious way, but at the same time it can cause problems like the one that lead to us coming in to contact with it.